This post is also available in: Français Español العربية فارسی Русский Türkçe

Was there enough room in the extermination areas of the Operation Reinhard death camps to crush any bones that remained after cremation?

Holocaust deniers claim:

There was not enough room in the extermination areas of Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor to crush the bones that were left after cremation.

For example, the self-named “Denierbud,” an American Holocaust denier and YouTube video maker, asks about Treblinka: “Where did they crush and sift the burnt remains of a population equivalent to San Francisco?” He asserts that bone crushing would have taken too long and required an area the size of a football field. He claims that the “falsehood of this whole story” comes out when maps of the camps are examined; the maps show there was not enough space for bone crushing in the extermination areas. Ultimately, Denierbud asserts that the whole process was impossible. It is just a “story” and the “storytellers didn’t always think of the best solutions for things.”[1]

The facts are:

Holocaust deniers simply speculate about the lack of space for bone crushing at the death camps of Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor. The evidence shows that there was plenty of space for this gruesome task.

What we know about the crushing of bones:

Chil Rajchman (also known as Henryk Reichman), a survivor of Treblinka who worked in the death camp area, recalled: “The body parts of the corpses that had been incinerated in the ovens often kept their shape . . . The workers of the ash commando had to break up these body parts with special wooden mallets . . . Near the heaps of ash stood thick, dense wire meshes, through which the broken-up ashes were sifted, just as sand is sifted from gravel. Whatever did not pass through was beaten once more. The beating took place on sheet metal, which lay nearby . . . [the] ash had to be free of the least bit of bone and as fine as cigarette ash.”[2]

Pavel Leleko, an Ukrainian guard at Treblinka, also testified about the bone crushing process: “After the bodies had been burned, the prisoners belonging to the ‘working crews’ passed the ashes through a sieve. The parts of the body that had burned but had preserved their natural shape were put into a special mortar and pounded into flour.”[3]

Denierbud’s speculations about the handling of the ashes:

Denierbud attempts to demonstrate that there was not enough room by diagramming three large black circular “ash piles,” each surrounded by a ring of eight blue, red, and yellow circles he calls bone crushing stations. He places all the circles on a football field to show how they would have taken up the entire field. Then, he searches for a similar, generously-sized area on the map of Treblinka and fails.[4]

Denierbud’s speculations raise more questions than they answer. How did he arrive at the dimensions for his imaginary circles? What are the dimensions? He simply slathers circles all over a football field. Why would the Nazis arrange everything in huge circles that used the most possible space? Why not just line up a few stations alongside the grills? He offers no proof for his figures or models.

The problem with Denierbud’s design for the ‘bone crushing stations’:

Denierbud uses a map of Treblinka from Yitzhak Arad’s study, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. On this map, Denierbud cannot find enough space for the bone crushing operations as he diagramed their dimensions. However, Arad’s map is not scaled and, therefore, cannot be used to accurately portray the size of the camp. Denierbud’s speculations about the amount of needed space is based on this map alone.

Peter Laponder undertook to reconcile the various hand-drawn maps of survivors together with aerial photographs. His map is the first attempt at reproducing the camp to scale and it shows plenty of space in the death camp section, space not occupied by mass graves, piles of sand, buildings, or cremation grids.[5]

A recent and more pertinent study, The Reconstruction of Treblinka by Alex Bay, is based on his scientific analysis of photographs and utilizes the most current diagramming technologies. Bay found that the extermination area could have held nine pits sufficient for 900,000 remains. His diagrams leave more than enough space for the gas chamber, cremation grids, and areas for crushing burned remains.[6]

How long it would take to crush the final remnants of bone?

Denierbud calculates that every station could crush one body every 3 minutes; 20 per hour; 200 per day if they worked 10 hours. Thus, one of his stations could have crushed a total of 1,600 remains per day.[7]

However, in his own experiment Denierbud leisurely crushed the remains of a 12.5 pound leg of lamb in about 10 seconds.[8] Given the weight of the actual remains (25 kilograms or 55 pounds on average), the ashes of one body could have been crushed in less than a minute—not the 3 minutes he calculates. That translates into 600 remains per day if only one Jewish prisoner was assigned to the task. However, we know that historically the work groups in the extermination area of Treblinka numbered over one hundred men at any given time. Clearly, there were plenty of prisoners available to crush the remains efficiently.

Evidence about the handling of ashes:

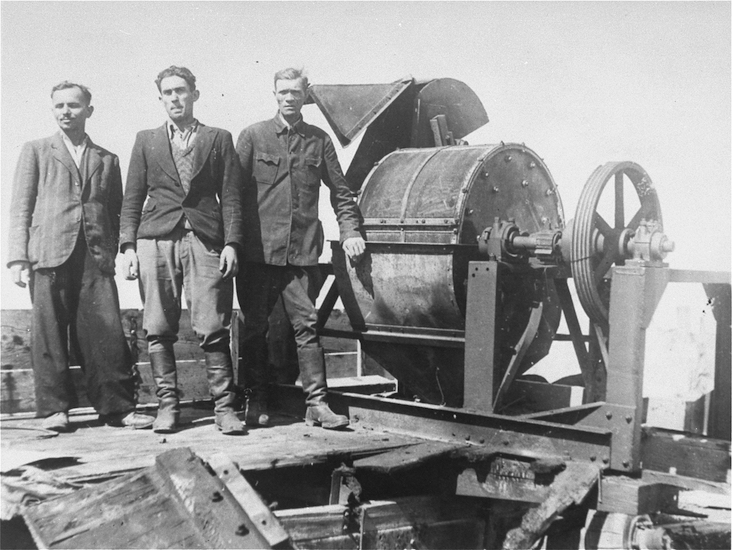

After a cremation grill cooled off, the ashes would be raked off to a side area for crushing and sieving. Large remnants of bone would be returned to another grill for more cremation. In some camps, such as Janowska, outside Lvov, Poland, a bone crushing machine may have been used. The ashes were then reburied in the empty graves.

There is documentary evidence about how the ashes were handled in Treblinka. Kurt Franz was the last commandant of Treblinka. Although photographs were explicitly forbidden by SS directive, Franz took numerous pictures of the camp. He made a photo album of his days at Treblinka, which he perversely named “Wonderful Times.” Franz photographed his SS colleagues, his dog Barry, and the animals in the Treblinka “zoo.” The album was discovered by German authorities in his apartment when he was arrested in the early 1960’s.[9]

Franz took several photographs of the excavators in the mass graves area. Alex Bay carefully studied Franz’s photographs and found two photos that show five probable ash heaps surrounded by Jewish prisoners who are apparently crushing and sieving the ashes. Another photograph shows a horse and cart near a series of ash piles, indicating that leftover parts might have been hauled some distance from the cremation sites for crushing and sieving. These photographs also show the general size of the death camp area, which was more extensive than Holocaust deniers maintain.[10]

Photo Credit: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Belarusian State Archive of Documentary Film and Photography

Conclusion:

If this matter were not so gruesome and terrible, Denierbud’s claims would be laughable. The crushing of remain bones was not a precision process, but it accomplished what the Nazis wanted: to destroy the evidence of mass murder as much as possible. Franz Suchomel, a guard at Treblinka, describes the situation well: “Treblinka was a primitive but efficient production line of death . . . Primitive yes. But it worked well, that production line of death.”[11]

NOTES

[1] “One Third of the Holocaust” at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=taIaG8b2u8I at approximately 3:10 to 3:16 minutes.

[2] Chil Rajchman, The Last Jew of Treblinka: A Survivors Memory 1942-1943 (Pegasus Books, 2011), p. 77.

[3] Robert Muehlenkamp, “Incinerating corpses on a grid is a rather inefficient method . . . “ at http://holocaustcontroversies.blogspot.com/2006/12/incinerating-corpses-on-grid-is-rather_18.html citing the interrogation of Pavel Leleko on February 21, 1945 at http://www.nizkor.org/hweb/people/l/leleko-pavel-v/leleko-002.html.

[4] “One Third of the Holocaust” at approximately 3:13 to 3:14 minutes.

[5] You may see this map at http://www.deathcamps.org/treblinka/maps.html (“New Treblinka Map,” August 1943.)

[6] Alex Bay, “The Reconstruction of Treblinka (“The Death Camp”) at https://archive.org/details/TheReconstructionOfTreblinka. See Figure 42, Projection of Mass Graves.

[7] “One Third of the Holocaust” at approximately 3:13 minutes.

[8] “One Third of the Holocaust” at approximately 3:11:20 to 3:11:30 minutes.

[9] See Yad Vashem archives at http://collections.yadvashem.org/photosarchive/en-us/39734.html.

[10] Alex Bay, “The Reconstruction of Treblinka” at https://archive.org/details/TheReconstructionOfTreblinka. See Figures D2 and D3.

[11] Franz Suchomel’s testimony in Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah. The film transcript is available in Claude Lanzmann, Shoah: The Complete Text of the Acclaimed Holocaust Film (Da Capo Press, 1995), pp. 52, 53.