This post is also available in: Français Español العربية فارسی Русский Türkçe

How do we know that possessions shipped from the death camps of Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor actually came from Jews murdered there?

Holocaust deniers claim:

The tons of clothing, personal possessions, and valuables shipped from the Operation Reinhard death camps of Treblinka, Belzec, and Sobibor do not prove that the camps were extermination facilities.

For example, Carlo Mattogno, an Italian Holocaust denier, states, “There is nothing in the documents themselves to indicate that this material was actually the property of deported Jews.”[1]

The facts are:

There are numerous primary documents showing the theft of Jewish-owned valuables at the Operation Reinhard death camps; the Nazis and their collaborators stole the Jews’ possessions and then murdered them. Some of the documents in question include railroad shipping manifests, Nazi directives and reports, and eyewitness testimony.

Facts about the Theft:

The Nazis and their collaborators stole many material goods from their Jewish victims, including clothing, personal valuables, and everyday trinkets. More specifically, they stole: watches, pens, pencils, shaving utensils, pen knives, scissors, purses, feather bedding, blankets, umbrellas, baby carriages, handbags, leather belts, baskets, furs, eye glasses, mirrors, toys, coats, hats, shoes, underwear, and more. Even rags were to be recycled. They sorted these goods into larger collections and shipped them to relevant locations for wartime use.

All usable clothing and personal goods were sent to the Majdanek concentration camp in Lublin for disinfection and repair. After Majdanek, the goods were shipped to Germany for distribution. Gold (including good fillings and teeth), precious metals, gems, jewelry, and currency were sent by either armored car or a special railway car escorted by an SS guard.[2] Jan Piwonski, a railway worker in Sobibor, recalled these shipments:

I know that the Germans dispatched clothing from the camp, because I saw it being loaded into wagons and transports out of the camp. I also know they sent crates [. . .] [they] were 1 metre [39 inches] long and very heavy. I know the crates were very heavy because I weighed them myself. From the labels on the crates [. . .] I could make out they were sent to Berlin. The Ukrainians carried the crates into a luggage wagon and a German officer, armed with a submachine-gun, got into the same wagon. I learnt from the Ukrainian that the crates contained gold coins . . . [and] there might be expensive jewelry and precious stones inside.[3]

Primary Documentary Evidence:

Three railroad shipping documents show that 152 boxcars filled with clothing and shoes were sent from Treblinka to Lublin, Poland between September 9 and 21, 1942.[4]

A directive dated September 26, 1942, from August Frank, an official with the SS concentration camp administration department, codified the process of plunder. Specific goods were sent to specific locations:

- To be deposited into the German Reich Bank: German money, foreign exchange, rare metals, jewelry, precious and semi-precious stones, pearls, gold from teeth, and scrap gold.

- To be repaired and “delivered quickly to front line troops”: watches and clocks of all kinds, alarm clocks, fountain pens, mechanical pencils, hand razors and electrical razors, pocketknives, scissors, and flashlights.

- All underwear and clothing, including footwear, were to be sorted and valued. Underwear of pure silk was to be handed over to the Reich Ministry of Economics.

- To be delivered to the Main Welfare Office for Ethnic Germans: featherbeds, quilts, woolen blankets, cloth for suits, shawls, umbrellas, walking sticks, thermos flasks, baby carriages, combs, handbags, leather belts, shopping baskets, tobacco pipes, sunglasses, mirrors, table knives, forks, spoons, knapsacks, and suitcases made from leather or artificial material.

- Also handed over to the Main Welfare Office for Ethnic Germans: bed linen, pillows, towels, wiping cloths, and tablecloths.

- To be sent to the medical office: eyeglasses of every kind (exception: eyeglasses with gold frames were treated as rare metals).

- To be delivered to the Reich Ministry of Economics: valuable furs of all kinds.

Welfare Office for Ethnic Germans entrance, Litzmannstadt Branch, Adolf-Hitler Straße 119 (Łódź, 119 Piotrkowska Street). Hans Wagner, 1940. Bundesarchiv, Bild 137-056310 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons

Frank cautioned at the end of his directive: “Check that all Jewish stars have been removed from all clothing before transfer. Carefully check whether all hidden and sewn-in valuables have been removed from all articles to be transferred.”[5]

Head of the SS Economic and Administrative Main Office, Oswald Pohl, also sent a report, dated February 6, 1943, to SS-head Heinrich Himmler. In this report, he estimated the value of the clothing and goods that had already been systematically stolen from their former Jewish owners. The report is titled “Report on the realization of textile-salvage from the Jewish resettlement up to the present date.” The textiles in his report came from the Operation Reinhard camps and Auschwitz-Birkenau. Pohl arrived at the following figures: 97,000 complete sets of men’s clothing; 76,000 complete sets of women’s clothing; 89,000 pairs of women’s silk underwear; 2,700,000 kilograms of rags; 62,000 men’s pants; 132,000 men’s shirts; 31,000 pairs of men‘s shoes; 155,000 women’s coats; 119,000 dresses; 107,570 pieces of women’s underwear; 85,000 kerchiefs, and 111,000 pairs of women’s shoes. These goods were shipped from Lublin to various places in the Reich in 825 freight cars.[6]

Another report, dated January 5, 1944, came from Odilo Globocnik, head of Operation Reinhard. His report, sent to Heinrich Himmler, summarized the total value of the money and goods stolen from the Jews in the General Government (occupied Poland), including the camps of Treblinka, Sobibor, Belzec, Majdanek, and Auschwitz-Birkenau. The total value of the goods in German Marks was 178,745,960.59.[7]

Eyewitness Testimony:

There were many eyewitness who recognized the theft for what it was.

For instance, Oskar Strawczynski, who worked in the reception area of Treblinka, recalled:

Blankets and tablecloths are spread on the ground and all kinds of goods are collected on them. There is a huge quantity and an astonishing variety: from, the most expensive imported textiles, to the cheapest cottons, from the most elegant suits, to the cheapest worn-out rags. There are avenues of suitcases and in them everything imaginable: haberdashery, cosmetics, drugs—it seems there is no article in the world that cannot be found here. The sorted items are brought to one side of the square where they are piled into huge bales [ . . . ] A special spot is designated for suitcases with valuables. They are filled with precious gold, jewelry, chains and watches, bracelets, diamond rings and plain gold rings—most of all wedding rings. There are treasures in foreign currency—gold and paper dollars, pounds sterling and old Russian gold coins. Polish money is hardly worth mentioning; it is stacked up in mountains. From time to time the “Gold Jews” who sort these treasures appear. They remove the filled suitcases and replace them with empty ones. These too are quickly filled.[8]

Another witness was Dov Freiberg, who survived Sobibor. He wrote:

We loaded the empty boxcars with all of the sorted items that had been collected in the barracks and warehouses [. . .] Boxcar after boxcar was filled with clothes, shoes and other useable items that Jews had brought with them to Sobibor. Everything was sorted and packed, toilet soap separate from laundry soap, men’s socks separate from women’s stockings, dolls separate from other toys. Even the rags were packed in large packages. Gold, silver and other valuables were packed in suitcases and special boxes, locked and loaded onto a special boxcar. Although we ran while we worked, without resting for a moment, the work took all day, until evening.[9]

Samuel Rajzman, a survivor of Treblinka, kept records of the railway cars that left the camp: 248 railway cars of clothing, 100 boxcars of shoes, 22 boxcars of material, 260 boxcars of bedding, 450 cars of various articles and household goods, and hundreds more cars with various rags. In all, Rajzman estimated the number of boxcars at about 1,500.[10]

Franciszek Zabecki, a Pole who worked in the railway station at Treblinka, testified that he counted more than 1,000 cars full of belongings that passed through the station.[11]

For approximately three years, from January 1942 onward, Ernst Gollak worked as an SS man in the SS clothing workshops at Lublin. Gollak later remembered:

From May or June 1942, in this clothing camp of Lublin, furs and coats of Jews who were in the extermination camps of Belzec, Treblinka, and Sobibor were disinfected and sent to Germany. These articles were brought by freight trains, unloaded by the ‘Ukrainian’ auxiliaries and later by the working Jews, disinfected, and loaded again in the freight cars [. . .] I once saw on the freight cars the names of the train stations: Berlin, Glogau, Breslau, and Hirscherg [12]

Thus, the eyewitness testimony of Polish bystanders, Jewish survivors, and German perpetrators corroborate the primary documentary evidence.

What do Holocaust deniers say about the goods listed in the documents above?

Italian Holocaust denier Carlo Mattogno suggests that the clothing listed in the documents was actually damaged German army uniforms. He makes this claim based on one ‘bill of lading’ (dated September 13, 1942) for a 50 boxcar shipment from Treblinka to Lublin. The ‘bill of lading’ for these box cars was labelled as containing “articles of clothing of the Waffen-SS.” He claims that the Waffen-SS (an elite division of the Wehrmacht) had “no relationship to the Treblinka camp.”[13] Thus, they must have been uniforms needing repair.

Mattogno, in fact, misunderstands or misrepresents the inner-workings of the workshops in Lublin. These workshops were actually under the authority of the Waffen-SS until March 1943. After this date, they were formally transferred to Odilo Globocnik, the head of Operation Reinhard. Thus, in September 1942, the clothing and goods stolen from murdered Jews would have been handled by the Waffen-SS.[14] There is also no shred of evidence that these boxcars were filled with German uniforms. There is an overwhelming amount of persuasive evidence, including German documents, showing that these boxcars were filled with goods stolen from murdered Jews.

Regarding Oswald Pohl’s report of February 6, 1943, Mattogno dismisses this evidence by claiming that Pohl was referring to goods taken from “various camps,” rather than the specific Operation Reinhard death camps and other extermination camps.[15] Contrary to Mattogno’s dismissal of this report, Pohl was in charge of plundering Jewish goods from all locations in the General Government, including the camps and the ghettos. This especially includes the plunder taken from a number of infamous camps, such as the three Operation Reinhard camps, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Majdanek in Lublin. In his report, Pohl noted specifically that the materials came from the camps of Operation Reinhard as well as Auschwitz-Birkenau. Since Auschwitz-Birkenau was just starting its most intensive phase of industrialized mass murder, it is highly likely that most of the textiles came from the Operation Reinhard camps, which had been operating at full steam for some time. Further, in an affidavit provided after WWII, Pohl testified that there was no doubt that the clothing had belonged to Jews who had been “exterminated.”[16]

Conclusion:

Nazi documents and eyewitness testimony both claim the rampant plunder of Jewish property. In and of itself, this evidence does not conclusively prove homicidal gassings at the Operation Reinhard camps. On the other hand, Holocaust deniers have no basis for claiming that the material in the boxcars was simply German army uniforms. Eyewitnesses and documents point overwhelmingly to the fact that at least 1,000 boxcars filled with the clothing and wealth of some 1,400,000 murdered Jews were shipped out of the Operation Reinhard camps. The clothing was refurbished for use by Germans and the valuables were shipped to the Reichsbank in Berlin.

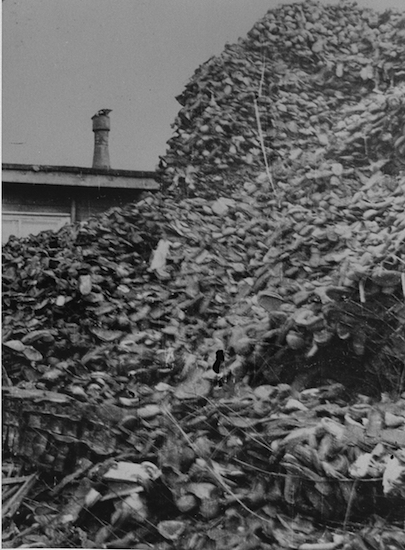

Photo Credit: United States Holocuast Memorial Museum, courtesy of Instytut Pamieci Narodowej

NOTES

[1] Carlo Mattogno and Jürgen Graf, Treblinka: Extermination Camp or Transit Camp? (Theses & Dissertations Press, 2004), 157 at http://vho.org/dl/ENG/t.pdf.

[2] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 154-164.

[3] Jules Shelvis, Sobibor: A History of a Nazi Death Camp (Berg, 2007), 191.

[4] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987),158.

[5] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 145, 555.

[6] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 160 citing Nuremberg Court document NO-1257. You may see excerpts from this report at: http://www.nizkor.org/ftp.cgi/camps/auschwitz/ftp.py?camps/auschwitz//documents/no-1257.

[7] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 160, 161 citing Nuremberg Trial document PS-4024. You may see this report at: http://www.mazal.org/NO-series/NO-0062-000.htm.

[8] Israel Cymlich and Oskar Strawczynski, Escaping Hell in Treblinka (Yad Vashem and the Holocaust Survivors’ Memoirs Project, 2007), 135, 136.

[9] Dov Freiberg, To Survive Sobibor (Gefen Publishing House, 2007), 222.

[10] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 158 citing Rajzman’s testimony in the Yad Vashem archives, 0-3/547, 157.

[11] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 158.

[12] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 159 citing a document from the Sobibor-Bolender Trial, Band 8, pp. 1556-1557. Note that Gollack uses the words “extermination camps.”

[13] Carlo Mattogno and Jürgen Graf, Treblinka: Extermination Camp or Transit Camp?, 157.

[14] Yitzhak Arad, Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps (Indiana University Press, 1987), 159.

[15] Carlo Mattogno and Jürgen Graf, Treblinka: Extermination Camp or Transit Camp? , 160.

[16] Joseph Poprzeczny, Odilo Globocnik: Hitler’s Man in the East (McFarland & Company, 2004), 260-261.